Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 2015

Sun bleaches this scarred desert-like landscape. Seemingly devoid of life, but I look closer and see lizards scurrying across the sand, and outcrops of saw grass. Behind the Mosque I find a little oasis. The last patch of water on what once was a huge lake. Thousands of families used to live here, it provided sustenance and money. But now it is gone and entire families have been uprooted. Today dilapidated buildings surround the empty lake. There’s a baby lying on a dirty mat, her parents are outside rummaging through garbage for recyclables. A man watches me from the first-floor balcony, behind him are murals painted by itinerant street artists.

Boeung Kak used to be the largest wetland area in metropolitan Phnom Penh. The lake and its surrounding areas occupied over 133 hectares and was home to approximately 17,000 people. Controversially, in 2007 it was leased to a shadowy private development company called Shukaku Inc. a company allegedly owned by a member of the ruling government. The entire process of acquiring the land was done with little oversight and transparency, the process was shrouded in mystery. By 2010 90% of the lake had been drained and filled with sand dredged up from the Mekong river. Thousands of families were forcibly evicted, many of whom received inadequate compensation if any at all. For those who fought, some were arrested and detained. Amnesty International called it the largest forced eviction since the Khmer Rouge evacuated Phnom Penh in 1975. For those residents that accepted relocation, many complained of a lack of basic infrastructure and poor soil conditions.

Boeung Kak Lake is illustrative of the unbridled and unchecked growth in Cambodia. Land grabs have become endemic in Cambodia. As the nation develops, unscrupulous developers collude with corrupt government officials to stake out a claim in this new ‘frontierland’. In a country where rule of law is very much a foreign concept, little recourse is available for residents who are out to seek justice and compensation for their land. This is modern Cambodia, a confusing amalgam of systems. On the one hand, it is a Constitutional Monarchy, run by a Communist government implementing an unabashedly free market economy. The pockets of officials are lined with silver, they surround themselves with largesse, all the while the proletariat suffer. This is the reality of Cambodia, there is no ‘trickle down’ effect to speak of.

Phnom Penh is a landscape of concrete and steel, fuelled by foreign investment, and built by an underpaid and undereducated rural workforce. Behind a beautiful French colonial era building I find children carrying building rubble at a demolition site. I ask the foreman whether the children went to school, he assured me they did but I remained sceptical. Poor rural families have no choice but to take their children out of school and send them into the workforce, they become breadwinners.

One night on a ride back home, my taxi driver lamented the state of his country. He described the corruption euphemistically as a ‘family business’. Nepotism and cronyism runs deep through the administration. This system of patronage predates the current regime, in fact ordinary Cambodians are used to it according to my taxi driver.

Back at the lake Panet (16 years old) said to me rather despondently “I don’t have money, because of empty water”. It seems their lives and livelihoods were so intimately intertwined together with the lake. The lake provided them with food and money, but now it is gone along with their hopes and dreams.

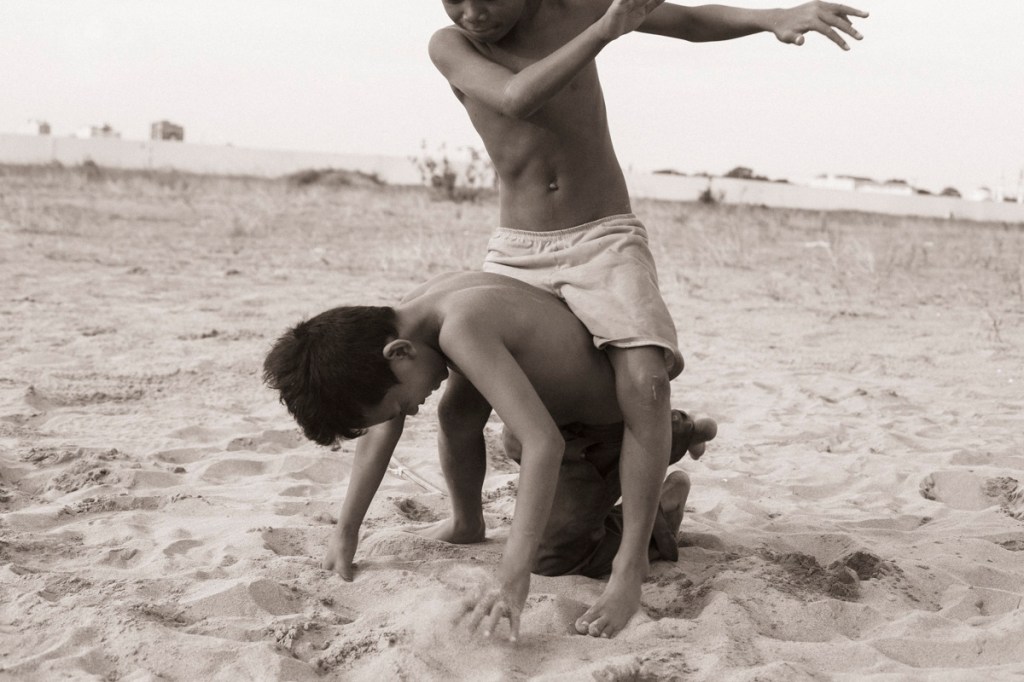

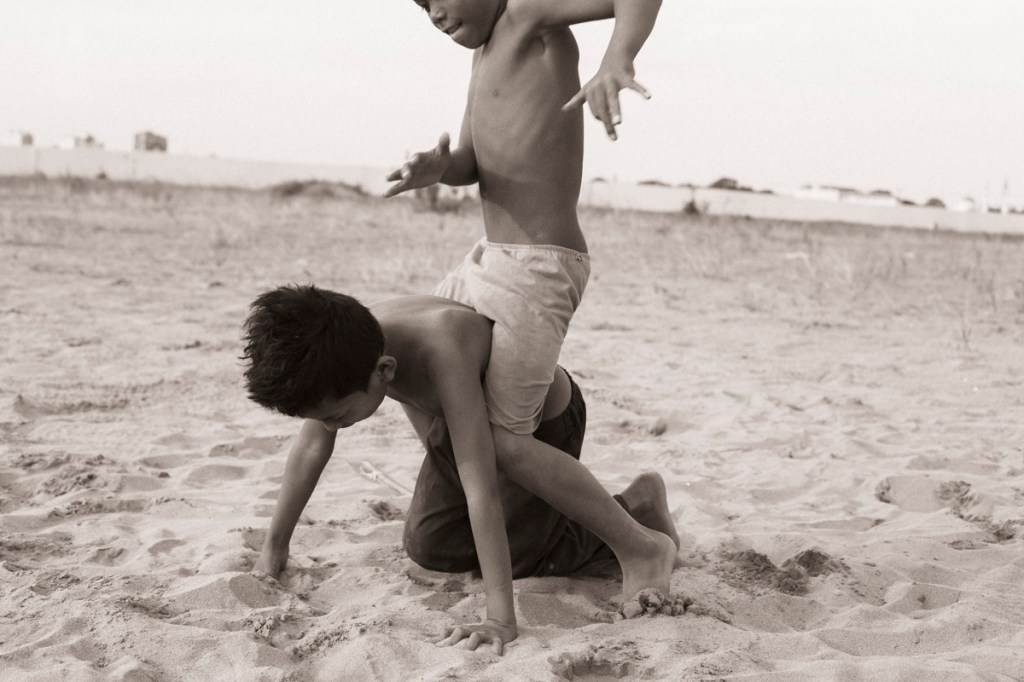

The boys sit there on top of the dunes surveying the vast empty landscape. Suddenly without notice they begin chasing each other, tossing and tumbling over the sand dunes.

I ask them “what do you want to be when you grow up”? A few of the boys tell me they want to be policemen or teachers, while Yong Savon points to the cranes in the skyline and says that he wants to be an engineer.

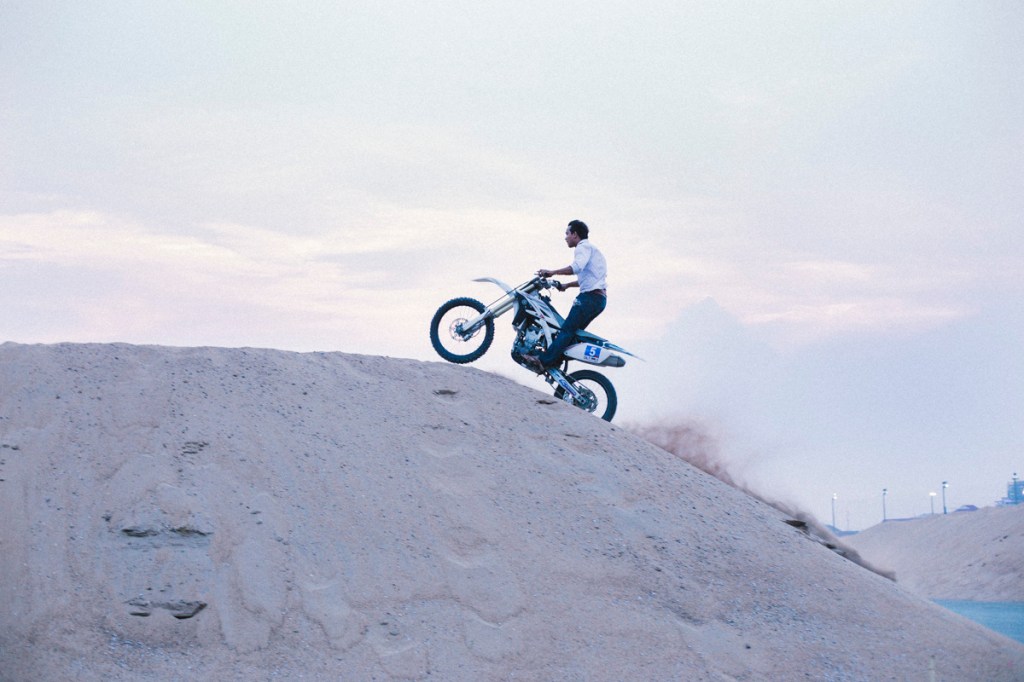

I hear the whirring of engines. I run up the steep side of the sand dune and upon reaching the summit I see a cloud of dust and sand.

Boeung Kak Guesthouse, a dilapidated shell of a building. The only residents are squatters and the homeless. There is a baby lying on a dirty mat, her parents are outside rummaging through garbage for recyclables. A man watches me from the 1st floor balcony, behind him murals painted by itinerant street artists.

He stands there confidently with an air of defiance. I am drawn to the stick that lies delicately balanced on his left shoulder. Earlier he pointed it at me as if it were a weapon, but now it resembles a sun-bleached bone white ornament.

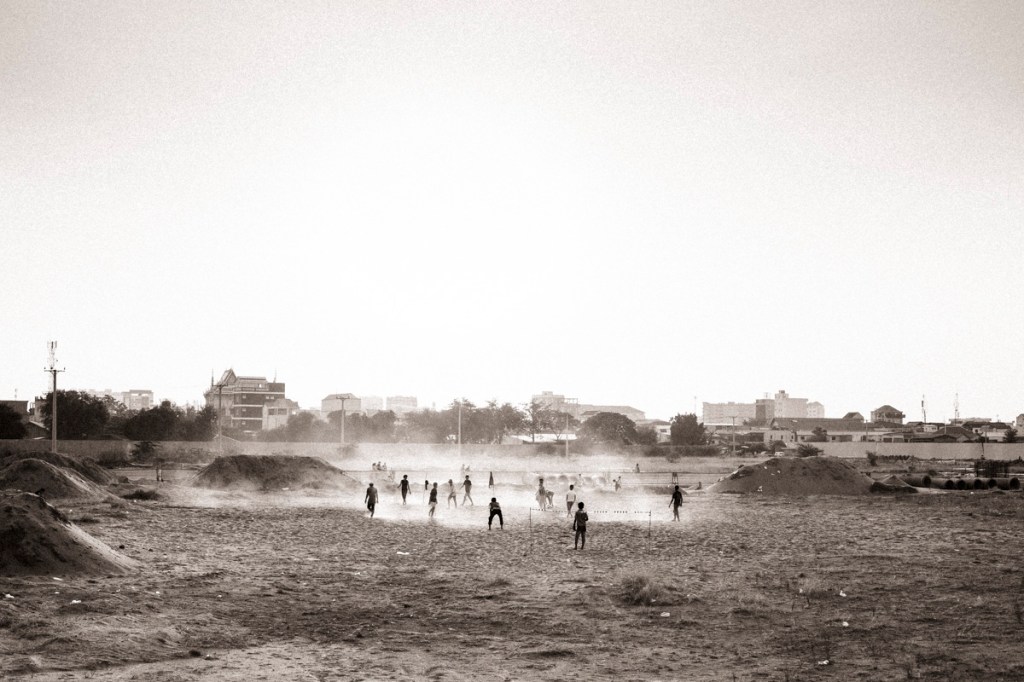

As the sun sets, local villagers come out to play football – two sticks and a piece of string is all they need. Just a few hundred metres away, wealthier folk play football in a state-of-the-art outdoor facility.

White featureless walls divide the barren landscape. Smoke rises from the heavy machinery — and so the lake begins its transformation.

He circles me on his motorbike, kicking up dust and gravel. He goads me. The other boys watch and laugh. Today he is king of the lake.

Sun bleaches the scarred desert like landscape. Seemingly devoid of life. But I look closer, and I see lizards scurrying across the sand, and outcrops of saw grass.

The wind is strong now and carries sand over the dunes. I see dark clouds and lightning in the distance. But for now I watch the setting sun turn the clouds a vibrant kaleidoscope of colours.

© 2015 De Sheng Lim All Rights Reserved.